Disclaimer: Any views expressed in the below text are the personal views of the author/s and do not constitute investment advice or recommendations for investments. The author/s views should not form the basis for making investment decisions - invest in markets at your own personal risk after performing thorough due diligence.

September 15th, 2008, was a day that reminded the world that nothing is too big to fail. Hundreds of suits filed out of the front doors of the collapsed bank, laden with cardboard boxes. Many never expected this day to come.

The collapse of Lehman Brothers was the climax of the subprime mortgage crisis in the USA. This single event had widespread repercussions, with contagion spreading to every corner of the globe, culminating in over $2.3 trillion in market value loss with an almost unquantifiable loss in global economic output. At the time of the collapse, Lehman was the fourth largest investment bank in the United States with 25,000 employees, $659 billion in assets and $613 billion in liabilities alongside a peak market cap of $60 billion.

Lehman Brothers were the largest holder of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) throughout the housing market boom during the early 2000s. By 2008 from an equity position, the bank had acquired real estate holdings nearly 30x larger than their cash-to-hand. Their balance sheet showed $659 billion in assets supported by $22.5 billion in collateral capital. A small 3-5% swing in real estate prices would lead to one of the largest liquidation events in history.

In simplistic terms, the balance sheet of Lehman was akin to opening a 30x cross-leverage Bitcoin long position with a $22.5 billion wallet balance, no stop loss, no take profit, then stepping away from the computer and going on an interrail trip across Europe with no internet access. Once arriving back from Europe after several months of soul-cleansing time away from the charts, you realise your positions are down 77% (the value loss of the Lehman stock in the first week of September 2008). You then try to sell your 30x leverage long positions but realise there is not enough liquidity in the market and no one willing to buy doomed positions off you – you’re riding the titanic into the depths of the Atlantic. RMS Carpathia doesn’t exist in this version of reality - nobody is coming to save you.

For the less financial jargon inclined reader, they were without a paddle.

Figure 1 - Lehman share price chart during 2008 with key events.

As defaults on subprime mortgages rose steadily, various fund managers started to take short positions in the market (Michael Burry of Scion Capital being the most famous thanks to the movie ‘The Big Short’). Investors started to question the real valuation of Lehman’s mortgage portfolio, leading to some sharp selloffs in their stock. The final straw was September 15th 2008, after rescue deals from both Barclays and the Bank of America fell through. Lehman Brothers was forced to file for bankruptcy – the largest corporate bankruptcy filing in US history. Barclays and Nomura holdings eventually acquired the majority of the investment banking and operations departments of Lehman, with Barclays also acquiring Lehman HQ in New York.

Figure 2 - Dow Jones Index key events during the financial crisis - axes labelled.

The collapse of Lehman was one of the triggers of the global financial crisis of 2008. Lehman was allowed to fail as the government refused to offer aid with the most troubled assets. Many still question this decision; however, various parallels can be seen with the recent implosion of Terra USD (UST) and Terra (LUNA) within the digital asset markets.

The 10th and 11th of May 2022 saw crypto suffer its ‘Lehman moment’, and though history does not repeat itself, it certainly rhymes.

A Precarious Relationship

Few success stories in the crypto space are as movie worthy as that of Terraform labs. Founded in January 2018 by Daniel Shin and Do Kwon, Terraform Labs is the developer of the Terra blockchain network and the Anchor protocol, a cross-chain DeFi application providing high yield through pooling and stabilising the emissions from several proof-of-stake blockchains. The rationale for starting Terra is almost a meme at this point: “to drive the rapid adoption of blockchain and crypto through a combined focus on price stability and usability.” This should sound like a familiar proposal as most projects are working towards similar goals. Terra did, however, set itself apart by making a stablecoin (UST) an integral part of the ecosystem.

If we view the digital asset arena as a rapidly evolving organism, stablecoins are its lifeblood. Though Bitcoin is the beating heart in terms of relative valuation and liquidity, its applications are limited beyond a store of value from an ecosystem or infrastructure standpoint. Stablecoins provide investors and protocol users with a haven to ride out the waves of volatility that characterise the crypto space.

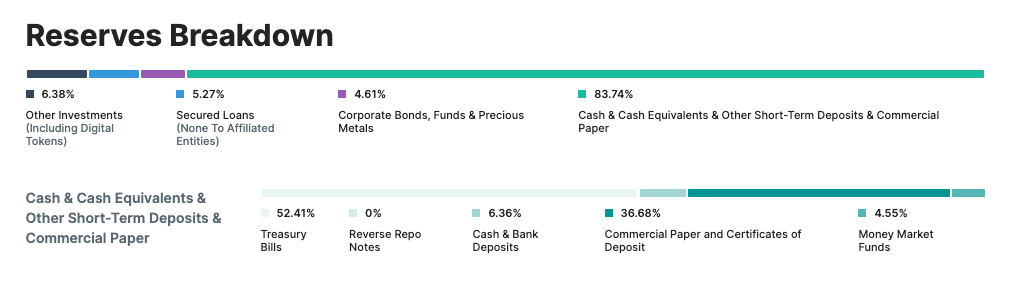

Stablecoins seek to hold their value at a predefined point, generally 1 USD at a 1:1 peg ratio. The way that stability is achieved varies depending on the coin. Tether and USDC are backed by reserves of US Dollars and other assets. Each USDT or USDC is pegged to the value of a dollar by the equivalent value of assets held in reserve. Other stablecoins, such as DAI, maintain stability through collateralisation. Traders and DeFi users can mint DAI stablecoins by depositing Ether into the MakerDAO protocol. This amounts to a loan, as the DAI must be paid back and with interest should the depositor wish to retrieve their collateral. Depositors also receive Maker governance tokens, allowing them to participate in the oversight of the DAI protocol.

Figure 3 - Tether (USDT) reserves breakdown - from Tether webpage.

In the decentralised world of blockchain, there are myriad issues with asset-backed stablecoins and fully backed stablecoins. This is mainly attributable to the custodians of the assets (such as Circle or Tether) becoming points of emergent centralisation as capital begets more capital. To a degree, the same could also be said for MakerDAO, holding large ETH deposits. This is seen as antithetical to some in the DeFi and crypto space and was the problem the team at Terra was trying to solve. A decentralised economy needs decentralised money. UST was supposed to be that money, and it arguably was, right up until it wasn’t. It failed in a spectacularly brutal fashion.

UST maintained stability through a mutually dependent pairing with Luna, the token that powered the Terra blockchain. This pairing meant that every time a TerraUSD token is minted, the amount equivalent to $1 of Luna is burned, and vice versa. The incentives around burning and minting are where the algorithmic element of the protocol comes in, with adjustment happening on an automatic and dynamic basis depending on UST price action. When the value of one UST dropped below $1, traders were incentivised to burn UST in exchange for a dollar in Luna. This reduces the circulating supply of UST, which increases the price of the token, assuming that demand remains the same. Conversely, if the value of one UST rises above $1, traders are incentivised to burn Luna in exchange for UST, increasing the circulating supply and driving the token price down.

This method of maintaining price stability is enticing, as it allows for a far greater degree of decentralisation than USDT or USDC, yet it is not without risk. Game theory and users acting rationally are integral concepts to understand when considering algorithmic stablecoins. These types of tokens are only stable if the peg can be maintained, which, in turn, relies upon traders engaging in the correct/assumed behaviours at the right time as decided by the algorithmic stability mechanism. This generally won’t be an issue with the right economic incentives. Engaging in behaviours that benefit the protocol also helps the user, therefore, doing so is inherently rational. Yet sometimes, market conditions are not conducive to rational decision-making, particularly during extreme stress or black-swan events.

Many criticisms around algorithmic stablecoins focus on the lack of backing of the assets and the need for users of the protocols to act in a way that reality will most likely deviate from. Due to UST’s rapid growth, much of this criticism has been levied at Do Kwon and Terraform Labs. Kwon was undeterred by the critics and recently began purchasing vast amounts of Bitcoin to hold as reserves to back UST.

Purchases amounted to more than $1.5B in Bitcoin, with further acquisitions of similar size planned by the Luna Foundation Guard (LFG), a non-profit organisation that supported UST and Luna. On top of this, the Terra Protocol intended to purchase the next $7B in Bitcoin from users willing to exchange their Bitcoin for UST.

The above did not happen.

The Lehman Moment

On the 7th of May, things kicked off with massive sell pressure on the Curve Finance protocol. Curve operates a liquidity pool called the 3Pool, or Tri-Pool. This pool holds a considerable amount of the available liquidity (around $3.4b) of the top three stablecoins in DeFi: USDT, USDC, and DAI. Combined with the various liquidity optimisations Curve has deployed, this deep liquidity means the 3Pool often provides the most capital-efficient route for swapping any of the big three stables. At the time of the attack, UST liquidity was also being moved in preparation for deploying the upcoming 4Pool. The 4Pool was to consist of UST, FRAX, USDT, and USDC. Maintaining the stability of the liquidity pool and the ratios of the stablecoins contained within is integral to the stability of the broader DeFi ecosystem. The interim 4Pool consisted of 50% UST and 50% 3Pool liquidity. Therefore, when someone swapped $85 million UST to USDC, that delicate balance was broken. Liquidity providers confidence was shaken, causing them to begin to pull their 3Pool liquidity, further skewing the ratios to a low of 77% UST and 23% 3CRV.

This initial series of transactions and swaps had UST sitting between 98.7c and 99.5c - below the $1 peg. When a stablecoin trades below its peg, it’s not always an indicator of an imminent death spiral, and the ratios in the liquidity pool did also nearly recover. This particular recovery was, however, short-lived. Further destabilisation soon followed.

On May 8th, the Luna Foundation Guard (LFG) tried to stem the flow of water onto the sinking ship. They began deploying their $1.5 billion worth of reserve capital. This consisted of a $750 million loan of BTC to market makers to be sold in defence of the peg and loaning another $750 million of UST to repurchase the BTC once volatility had normalised. A potentially solid strategy if confidence had been restored, yet that was not the case as Anchor protocol saw over $2.8 billion in outflows. Deposits fell 20%, and the price of Luna began dumping. The ship was sinking fast, and the dry powder was being exhausted.

By May 9th, the sinking had begun to accelerate. UST fell to 60c on Binance, with the exchange subsequently blocking bids below 70c. The on-chain liquidity for UST had all but evaporated, with the ratio of UST to 3CRV finishing the day at 95:5. This enormous loss of liquidity began spreading to other Curve pools, and the panic saw a further 3.8 billion UST withdrawn from Anchor. To make matters worse, UST flipped Luna in market cap. This meant the mint and burn mechanism designed to maintain the peg ceased functioning as intended. The limited liquidity of UST and the devaluation of LUNA meant there simply wasn’t enough money in the system to support redemptions.

From May 10th to 12th, the Titanic slipped below the surface, swallowed by the abyss. UST depegged yet again, on-chain liquidity was nothing more than a puddle, and Anchor depositors were getting out any way they could. Since the start of the fiasco, 84.49% of Anchor users had abandoned ship. With this little liquidity remaining, the only remaining exit was through minting new LUNA and market selling, which led to the supply of LUNA hyperinflating to 32 billion tokens from 386 million. This 8190% increase in supply cratered the price from $31 to less than 1c. Over the course of a little more than a month, $41 billion in value had evaporated.

This simultaneous hyperinflation and value loss period introduced another very real and present danger - the increasing economic viability of a 67% attack. At times of normal function, this kind of attack is not financially viable as the cost of acquiring this many tokens is beyond prohibitive, but these times were not normal. To prevent this, the Terra blockchain was stopped, and Terraform Labs proposed a 240 million token increase in the amount of Luna staked. A burn of 1.4 billion UST was also proposed, effectively reducing the supply by 11.8%. This proposal came at the same time as rumours were circulating that LFG was seeking bailout money from market makers and trading firms. This may have been successful were it not for Coindesk revealing in a news story that this wasn’t the first algorithmic stablecoin failure that Do Kwon had presided over - Basis cash had seen a similar, if not as spectacular, fate as what was unfolding with UST.

The broader crypto market also began to experience some of this unprecedented turbulence. Tether (USDT) has long been the subject of FUD, and fears of stablecoin contagion were rife. The 3Pool was all but dry of USDC and DAI, and liquidity for USDT was evaporating too. The price of USDT dropped to 95c on May 12th, offering a free haircut to those seeking alternative safe havens. Thankfully volatility subsided, and the peg was found again for USDT, and over the next few days, the loss of one of the most important protocols in the space began to be forgotten with no major financial or economic ripple effects other than a healthy dose of PTSD for those left holding the bag.

The Prime Suspects

Social media (as ever) has been rife with speculation as to what occurred with UST/LUNA, with many outlandish theories and ideas being spouted by self-proclaimed investigative financial journalists with ten followers and three-week old Twitter accounts. The question we all want to know the answer to – was this event driven by shadowy actors in a malicious exploit, or was it simply a structural weakness in a young, growing and largely experimental stablecoin ecosystem.

Perhaps the only credible theory that has come to light is the idea of an already existing vulnerability being exploited and orchestrated by Blackrock and Citadel. Both firms were involved in the GameStop (GME) short squeeze and therefore had a previously proven involvement in nefarious market activities (that we know of). To keep this piece short, we won’t do a deep dive into the questionable acts surrounding the January 2021 GameStop story. It was a key event that drew unwanted attention to some of the market fixing and manipulation that goes on at the top by various asset managers and hedge funds in an attempt to steamroll the average retail trader. Simply put, we are their exit liquidity.

Secondarily to add further fuel to the bonfire in this speculative theory of exploitation –Blackrock recently became the primary reserve manager for the cash reserves of another stablecoin (USDC), managed by Circle and Coinbase; whilst tactically investing in Circle’s $400M funding round. Therefore UST/LUNA became a direct competitor to a large Blackrock investment in early 2022.

The theorised vector of the attack was as follows (we will refer to both Citadel and Blackrock as the “coalition”) and maps surprisingly well onto the previously mentioned series of events:

The coalition borrows 100,000 Bitcoin from an anonymous OTC desk/donor/Exchange. It is important to note that we do not know when this occurred. It could have been weeks or days before the attack.

They then trade 25,000 Bitcoin for UST and open a Bitcoin short.

The remaining 75,000 Bitcoin are used to tactically market sell and short into thin order books to crater the market and cause a large liquidity event/cascade.

This causes Bitcoin prices to reach $30,000 with no relief in sell pressure whilst the coalition pocket the profits (in UST) from their now extremely profitable shorts.

They then start attacking UST, selling violently into the open market against any pairing (likely another stablecoin, and based on the events detailed above, possibly the initial 85 million UST to USDC swap).

LFG is now forced to sell their Bitcoin reserves at market, thereby taking significant losses in an attempt to recover the UST peg. This only serves to dump the price of Bitcoin further whilst a bank run occurs on UST and Anchor as people begin panic selling and dumping the peg further, leading to a feedback loop.

The coalition has been shorting this whole move and likely banking huge profits whilst taking a major USDC competitor out of the game, potentially permanently.

Both Citadel and Blackrock have since emphatically denied any involvement in these events, and the above is nothing more than speculation based on what we already know to be true. That being said, ‘history never repeats itself, but it often rhymes’.

The Regulatory Forecast

Regulators are starting to believe that stablecoins need their own version of the Basel III agreements, which govern global banks. The critical issue here is that we cannot have efficient self-regulation in a permissionless environment – the bad players simply won’t regulate themselves. Perhaps what is needed is a movement away from the high APY stablecoin schemes and a concerted move to coins such as USDC, DAI, RAI and LUSD.

Directionally, we’re getting to the point where bulls are few & far between. As regulators accelerate their efforts to bring transparency to the stablecoin space, anyone even tangentially exposed to digital assets should be watching closely. This isn’t just true for crypto; it’s a feature of many markets – per the charts below, fund managers are more bearish, risk-off & hoarding more cash than they have done since the early 2000s.

Figure 4 - Fund manager cash levels showing a large peak to visualise the general risk-off sentiment in markets. Source: Bank of America - Global Research

Figure 5 - Fund manager risk appetite showing a clear drop in a similar fashion to 2009 directly after the financial crisis. Source: Bank of America - Global Research

Unlike previous periods of systemic risk-off sentiment, cash is now a terrible place to hide as high-single-digit inflation rages worldwide. At some point, custodians of capital will have to step into risky assets to avoid the bleed - we feel that holding large amounts of cash is akin to a melting ice cube in this environment. When that happens, Ethereum – the only yield-bearing asset which will be meaningfully deflationary in an inflationary world – will look particularly attractive. This isn’t to mention the ESG spotlight as the protocol transitions onto POS from POW. We will discuss this in further articles.

The Aftermath

The Terra ecosystem had nearly 10% of the total Defi TVL. It was bigger than the seven largest banks’ total % share in global banking. Imagine JPM, BoA, Citi, Wells Fargo, GS, and Morgan Stanley all going bust within a 48-hour window. That’s the level of systemic shock we just witnessed. The digital asset markets have shown remarkable resilience so far – if an event like this happened in traditional markets, it would be akin to the dinosaurs watching the meteorite impact back in the cretaceous period. Luna had a $41 Billion market capitalisation as of 04/04/2022 – this was 2/3rd of the largest size that Lehman Brothers was at peak.

Surprisingly, we feel that this event in aggregate, was bullish for the space. It’s remarkable that the collapse of an ecosystem worth $40B created no contagion whatsoever. When Lehman died, the entire global centralised financial system was brought to its knees and had to be bailed out with trillions in taxpayer money. Yes, there was selling across the board in cryptos as participants took risk off the table. Still, it’s important to highlight that nothing actually broke – no exchanges went bankrupt, no protocols disappeared (except for LUNA), and no critical crypto infrastructure was damaged. This reveals a robustness that critics have questioned in the recent past. That said, many crypto-native participants take this robustness for granted. While UST was not systemically important, other stablecoins are.

To further put the magnitude of the collapse into visual scale, Bitconnect is the only comparable event in crypto history. Bitconnect (BCC), first established in 2016, was an open-source cryptocurrency that was connected with a high-yield investment program. It was essentially a large scale Ponzi. After the platform administrators closed the earning platform on January 16, 2018, and refunded the users' investments in BCC following a 92% coin value crash, confidence was lost. The value of the coin plummeted to below $1 from a previous high of nearly $525. Below we can see the market cap of LUNA overlaid on the BCC market cap during both crashes.

Figure 6 - Overlay of the market cap destruction of Luna (blue) and Bitconnect (green) from 2018. This graphic offers perspective as to the groundbreaking move.

Risk management cannot be just a feature. It needs to be a core principle. This event has demonstrated a need for better risk management and insurance solutions. These will undergo dramatic improvement and evolution. As such, this event is the inflection point for an adoption increase.

We need to start doing more due diligence into the architecture and value accrual mechanisms of protocols. We need to be asking the tough questions and shining a spotlight on potential attack vectors. The destruction of LUNA, UST, and the Terra ecosystem was painful to behold, but it will not be without value if lessons can be learned.